Sunday School: Forgotten Faces of Flushing #24: The Pitcher They Traded for Keith: Neil Allen’s Underrated Mets Legacy

- Mark Rosenman

- Jun 15, 2025

- 5 min read

Welcome to the twenty-fourth installment of Mets Sunday School: Forgotten Faces of Flushing, our weekly meditation on the players who’ve slipped through the cracks of Mets history like sunflower seeds through the Shea Stadium bleachers. This is where we remember the names that don’t make the highlight reels or the bobblehead nights though, once in a while, they resurface on Old Timers’ Day, more curiosity than crown jewel.

Last week, we took a sentimental stroll through the late '70s to revisit Bruce Boisclair, the smooth-swinging lefty who played like being a Met still mattered even as the stands emptied and the losses piled up. He wasn't a star, but he was there. And if you were, too, you remember.

This week, we step into the early '80s, a transitional time when the franchise was trying to crawl out of the post-Seaver fog and reestablish a heartbeat. Amid this uneven rebuild, one young pitcher emerged with a rising fastball, a competitive streak a mile wide, and just enough flash to make fans believe the next Mets ace had finally arrived.

Let’s talk about Neil Allen, the confident, sometimes combustible right-hander who shouldered closing duties, moonlighted as a starter, and ultimately became the trade chip that brought Keith Hernandez to Queens. In a conversation I had with Neil back in the '80s a tape I still have he spoke with equal parts swagger and sincerity, the very mix that defined his time in Flushing.

He didn’t save the Mets. But for a few wild years, he kept them interesting.

Before closers were "closers"—before the entrance music, the smoke machines, and the chest-thumping theatrics—there was Neil Allen, charging out of the Mets bullpen in the early '80s with a hammer curveball, a goofy smile, and a heater that popped the mitt hard enough to wake up the ushers in the upper deck at Shea.

Allen didn’t just pitch for the Mets—he survived the early '80s Mets, which is a lot like saying you once lived in a haunted house but came out with a decent tan and all your teeth.

He gave the Mets three solid seasons as their main man in the ninth inning. And if the team had been even remotely competent in those years, he might’ve racked up twice as many saves. But as it stood, his 69 saves were second-most in franchise history when he was traded in mid-1983—ironically, for a guy who would help change the entire direction of the team. We'll get to that.

But first, let’s rewind.

Born in Kansas City, Kansas, in 1958, Neil Patrick Allen grew up in a household with three older brothers and a dad who couldn’t see but could still hear a missed pitch from the dugout. His father, Bob, legally blind due to retinitis pigmentosa, coached his son not by watching—but by listening. If he didn’t hear that sharp “thwack” of the ball meeting the glove, he’d shout, “Tempo!” from the dugout like a blind metronome with a heart full of baseball.

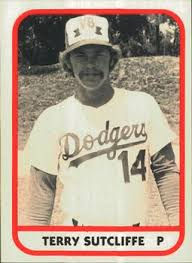

Neil grew up slinging both baseballs and footballs with equal velocity, starring as a quarterback at Bishop Ward High School. He had a football scholarship lined up at Kansas State, but one dominant pitching performance against Rick Sutcliffe’s younger brother changed the trajectory. The scouts came for Terry Sutcliffe—they left buzzing about Allen.

His dad gave him the nudge he needed. “Neil,” he said, “you’re not exactly a brain surgeon, and if football chews up your arm, what are you left with?” So Neil followed the cowhide.

The Mets drafted him in the 11th round in 1976 and gave him six grand to sign—about enough in those days to buy a car, which is exactly what Allen did. A 1976 Grand Prix with a T-top. I mean, c’mon—of course he did.

He worked his way up the Mets’ system quickly, with a curveball taught by his dad and the kind of confidence you can’t coach. By 1979, ready or not (spoiler: mostly not), he was pitching in the big leagues for Joe Torre’s Mets—a team so cash-strapped they were throwing unseasoned rookies like Allen, Mike Scott, and Jesse Orosco into the deep end and hoping they’d float.

Allen didn’t float at first. He went 0-4 as a starter. The kind of stretch that makes you question your career, your life choices, and possibly your car loan. But then, fate—always a bit of a trickster—stepped in. An injury kept him in the big leagues instead of shipping him out. And when Skip Lockwood went down, Torre rolled the dice and stuck Neil in the bullpen.

And wouldn’t you know it? The kid thrived.

From May 20, 1979, when he got his first big league win against the Phillies, to July 28, when he notched his first save against the Cubs, Allen started to look like a real-deal fireman. By 1980, he was the Mets' closer, piling up 22 saves and finishing 59 games. His stuff was legit—mid-90s heat and a curve that could have its own zip code.

Catcher John Stearns was practically giddy about him. “Top curveball in the business,” he said. And that guy didn’t toss compliments around lightly. Stearns would tackle a base-runner at second if it meant saving a run, so if he vouched for you, you were the real thing.

Allen saved 18 games in 1981, another 19 in ’82. And that was with the Mets rarely handing him a lead to protect. He was consistently among the top save-getters in the league despite pitching for a club that couldn’t get out of its own way.

But the wheels began to wobble in 1983. He coughed up some tough losses, including back-to-back walk-offs to the Phillies—one of them being the dreaded “ultimate grand slam” to Bo Díaz. That’s not a made-up term. It’s a walk-off grand slam in the bottom of the ninth when your team is down by three. Mets fans still wake up screaming about it.

Jesse Orosco took over the closer’s role, and Allen, struggling with injuries and personal demons, began drinking more. Some in the clubhouse chalked it up to nerves. Others, like Tom Seaver, didn’t think there was a real problem. But there was.

Allen was eventually diagnosed with emotional stress, though in hindsight—and Neil himself has admitted as much—alcoholism was a real part of the equation. Through it all, his affability, work ethic, and love of the game stayed intact. That says a lot about the man.

Then came June 15, 1983—one of the most important dates in Mets history. Neil Allen and Rick Ownbey were shipped to the Cardinals in exchange for a guy named Keith Hernandez. Maybe you’ve heard of him? Gold Glover. MVP. Mustache god. Co-captain of the '86 champs. Yeah, that guy.

Allen, for his part, took the mound for St. Louis at Shea just six days later. What’d he do? Tossed eight shutout innings against the Mets. If he felt any bitterness about the trade, he sure didn’t show it.

He’d go on to pitch for the Cardinals, Yankees, White Sox, and Indians, toggling between the rotation and the bullpen. He battled more off-field struggles, but he never stopped showing up. That was always Neil Allen: the guy who kept showing up.

And after his playing days were done, he didn’t fade away. Instead, he became a pitching coach—another act in his baseball life. From 1995 on, he helped young arms across the game, from minor leaguers to the big boys, rediscover their rhythm. Kind of fitting for a guy whose own father taught him the importance of “tempo.” One of the pitchers he influenced deeply was current Mets pitching coach Jeremy Hefner, who worked alongside Allen on the Twins’ coaching staff. Hefner credits Allen with helping shape his approach to both pitching mechanics and the mental side of the game—proof that even decades after throwing his last pitch in Queens, Neil Allen was still helping Mets pitchers find the strike zone.

Here are my interviews with Neil over the years :

Comments