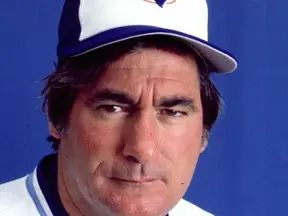

Saving Games, Then Saving Lives: Remembering Ron Taylor

- Mark Rosenman

- Jun 16, 2025

- 6 min read

Ron Taylor, passed away today at the age of 87, lived two lives—both extraordinary. One as a World Series–winning relief pitcher for the Miracle Mets of 1969. The other as a practicing physician who traded the bullpen for a white coat and became team doctor for the Toronto Blue Jays. He was, quite literally, Dr. Baseball.

Taylor’s major league career began with the Cardinals, where he helped St. Louis capture the 1964 World Series by tossing four no-hit innings against the Yankees. But his second chance at baseball glory came in Queens—thanks, in part, to a familiar face. After struggling to find his footing in Houston, Taylor felt underused and underappreciated. Mets GM Bing Devine, who had been with Taylor in St. Louis, came calling. “Can you still pitch?” Devine asked. Taylor’s answer was swift: “Absolutely. Just get me out of here.”

Devine did just that. On February 10, 1967, Taylor’s contract was sold to the Mets’ Triple-A club in Jacksonville. Less than two months later, he made the Mets’ Opening Day roster—and never looked back.

That first season in Flushing, Taylor was the bullpen rock, leading the team with eight saves in 50 appearances and posting a career-best 2.34 ERA. He was so stingy with the long ball that he didn’t surrender a home run until mid-April—and wouldn’t give up another for over a calendar year. For a franchise still figuring out how to crawl, Taylor was a steady hand.

“In New York, I finally felt like I belonged,” Taylor would say years later. “I worked my tail off, and the results showed.”

Of course, the results for the team weren’t quite as pretty. The 1967 Mets lost 101 games, the fifth time in six years they brought up the rear in the National League. Taylor, ever the dry wit, once joked that whenever it rained, half the clubhouse threw a victory party. But by 1968, things began to shift. With Gil Hodges now at the helm and a maturing young staff led by Seaver and Koosman, the Mets posted a then-franchise-best 73 wins. Taylor matched a club record with 13 saves and was among the league leaders in appearances.

That offseason, Taylor joined a group of big leaguers touring military hospitals in Guam, the Philippines, and later, South Vietnam—an experience that would quietly reshape his life. Amid the war-zone visits and conversations with combat medics, Taylor began contemplating his post-baseball future. Medicine, it turned out, had begun to call.

But first, there was one more miracle left in his right arm.

In 1969, the Mets were given 100-to-1 odds to win the pennant. No one outside their clubhouse believed. But Gil Hodges gave each player a clear role—and Taylor’s was simple: get outs, keep games close, and hand the ball to Tug. Taylor delivered. He pitched in 59 games, including a dominant stretch of 15 straight scoreless innings between May and June, as the Mets surged past the heavily favored Cubs and into first place.

In the playoffs, he was calm, efficient, and essential. Taylor earned the first save in League Championship Series history in Game One against the Braves, then came back the next day to notch the win in relief. One of his most memorable moments came that season when Hodges approached him with a curious decision: intentionally walk Hank Aaron to pitch to Orlando Cepeda. Taylor pushed back. “Let me face Henry,” he told his skipper. Hodges, whose temper showed when a certain vein in his neck popped, gave a terse warning: “You’d better get him out.” Taylor did. Aaron grounded out.

The Mets, of course, stunned the Orioles in five games in the World Series. Taylor played a key role, throwing scoreless relief in Game One and preserving a 2-1 lead in Game Two by retiring Brooks Robinson with two on in the ninth. Four days later, he sat in the dugout as Cleon Jones squeezed the final out in left. The Mets were champions. Taylor, soaking in the ticker-tape parade down Broadway, thought not of baseball—but of history. “MacArthur, Eisenhower, Kennedy… and now us,” he said. “It was surreal.”

Taylor would pitch two more seasons for the Mets, even earning the Opening Day win in 1970. He finished his career with brief stints in Montreal and San Diego before hanging up his spikes in 1972. But he wasn’t done.

He returned to Toronto and walked into the office of the medical school dean at the University of Toronto, looking to change careers at age 34. When asked what he’d been doing for the past 11 years, Taylor replied, “Playing major league baseball.” The dean blinked. “What’s that?”

No matter. Taylor re-enrolled in a full pre-med curriculum, pulling long days of class and even longer nights of study. “I’d sleep a few hours, then hit the books until sunrise,” he recalled. His grades, and grit, earned him a spot. He graduated from med school in 1977.

By 1979, Taylor was back in a big-league clubhouse—this time with a stethoscope. As the team physician for the Blue Jays, he patched up ballplayers, diagnosed injuries, and even threw occasional batting practice. He later opened a thriving general practice and a sports medicine clinic at Mount Sinai Hospital, where he met Rona Douglas, the nurse who became his wife.

Ron and Rona raised two sons, Drew and Matthew. Drew followed in his dad’s footsteps, pitching professionally and co-directing Dr. Baseball, the 2016 documentary that captured Taylor’s improbable double life.

Taylor’s collection of rings was as diverse as his career: two World Series titles as a player, two more as team doctor, one from the ’91 All-Star Game, and of course, his wedding band. Yet the one he always pointed to was his engineering ring—the understated symbol of hard work and intellect. “It’s the only one I wear,” he said.

Inducted into the Canadian Baseball Hall of Fame in 1985 and Canada’s Sports Hall of Fame in 1993, Taylor was also honored with the Order of Ontario in 2006. He retired from medicine in 2014 at the age of 76.

Reflecting on it all, Taylor once said: “I can barely name ten doctors or engineers I studied with. But I remember every teammate from the Mets and Cardinals. Those championship seasons—those are bonds for life.”

And just as those teammates made a lasting impression on Taylor, so did another figure in Mets lore: Ralph Kiner. In an interview I conducted with him for Down on the Korner: Ralph Kiner and Kiner’s Korner—the book I co-authored with fellow KinersKorner.com staff member Howie Karpin—Taylor spoke warmly about his experiences on the beloved postgame show.

Appearing several times on Kiner’s Korner, Taylor understood the quiet honor of being asked. “Just hearing Ralph mention your name meant something,” he recalled. “It was a kind of unspoken recognition.” For Taylor and many of his Miracle Mets teammates, a postgame invitation to the Korner was more than just an interview—it was a moment of validation.

The process was casual but meaningful. Kiner would simply approach you in the clubhouse after the game—no big announcement—and extend the invite. “I was always glad to do it,” Taylor said. “Ralph was a gentleman, always prepared, and asked questions from a player’s point of view. You knew he understood what had just happened out there.”

One appearance stood out in particular. After being struck in the head by a line drive and somehow turning the play into a double play, Taylor sat down with Kiner, who cued up the footage. “He said, ‘How do you feel? You just got a double play off your head.’ And I told him, ‘Yeah, that was fun.’” Taylor laughed at the memory. In an era before video access was common, seeing a play back on the studio monitor felt surreal—and having Ralph guide you through it made it feel big-league.

Though he couldn’t remember the parting gifts guests received, the experience of being on Kiner’s Korner left a lasting impression. “He never flaunted his own greatness,” Taylor said. “He just did his job and respected everyone around him.”

Ron Taylor was the rarest kind of figure in sports: a quiet hero in two professions, a man who helped his team when it mattered most, and then helped people far beyond the diamond. He may be gone, but for Mets fans—and for anyone who believes in second acts—his story will always be Amazin’.

Comments