Friday the 13th, George Foster, and the Night Kiner’s Korner Saved Bill Ladson's Life

- Mark Rosenman

- Sep 26, 2025

- 4 min read

Every so often in the press box, between the stale pretzels and the postgame scorebook math that makes you question whether you really passed third grade arithmetic, you stumble into a story that stops you cold.

That’s exactly what happened to me with Bill Ladson, the longtime MLB.com reporter and the man behind the “All Nats All the Time” blog. Bill’s been covering baseball forever, and if you’ve spent any time around him, you know two things: he’s got a heart the size of Shea Stadium and he’s got stories. Boy, does he have stories.

One night, Bill looked at the KinersKorner.com logo on my shirt, smiled, and said words I’ll never forget:“Kiner’s Korner saved my life.”

Now, I’ve heard a lot of things about Ralph Kiner’s legendary postgame show. It made people laugh. It gave players a chance to speak without a filter. It made Mets fans feel like part of the game even after the last out. But "saved a life" ? That’s a new one.

So I asked Bill to take me back.

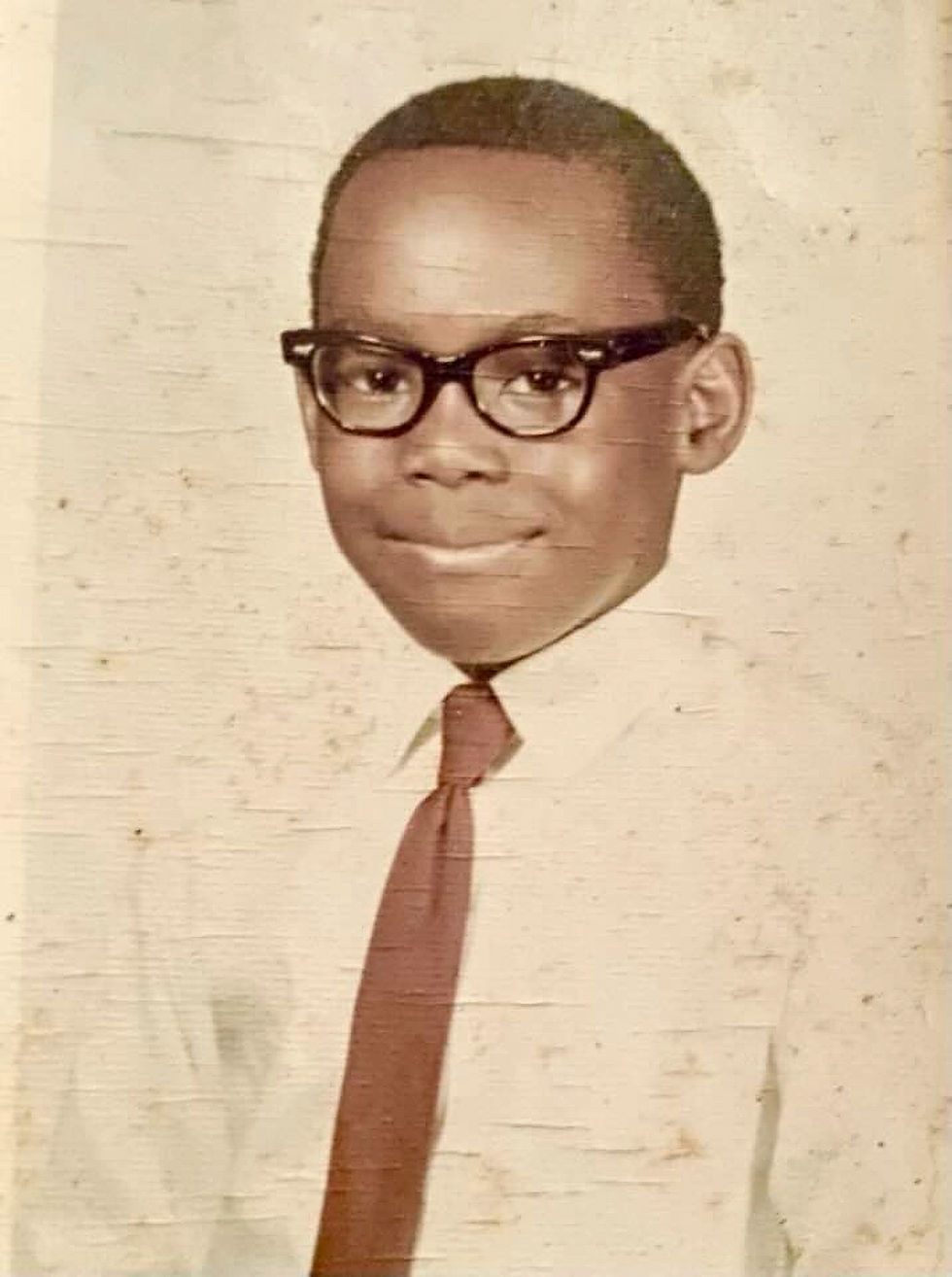

Astoria, Queens. Bill was a kid growing up in the Astoria Housing Projects, the son of a strong mother who never quite understood how her boy could fall in love with the Yankees, especially since they were one of the last teams to integrate. But that was Bill. At two years old, he was already transfixed by Joe Pepitone’s sideburns and swagger, and by the time he could ride a bike, he was a die-hard Yankees fan.

His hero? Thurman Munson. Not because Munson was flashy—he wasn’t—but because he worked like a dog behind the plate and in the batter’s box. That kind of grit stuck with Bill.

By the mid-70s, life in Queens wasn’t always easy, but baseball was the steady drumbeat in his world, along with music. Ask him today and he’ll rattle off his playlist: Otis Redding, King Curtis, Ray Charles, the Allman Brothers. The man might write about Juan Soto or Pete Alonso during the day, but at night, he’s just as likely to be lost in “Whipping Post” or “These Arms of Mine.”

But on this night—August 13, 1976—none of that mattered as much as catching Kiner’s Korner.

“There was a park festival going on in front of my window,” Bill remembers. “I went to my brother Kevin and said, ‘I’m going upstairs because I want to see who is on Kiner’s Korner.’”

The Mets had just lost to the Reds, 7–3, and Ralph Kiner’s guest that night was George Foster, who’d driven in four runs. So Bill and Kevin sat down to watch Ralph and Foster talk baseball.

And then the shots rang out.

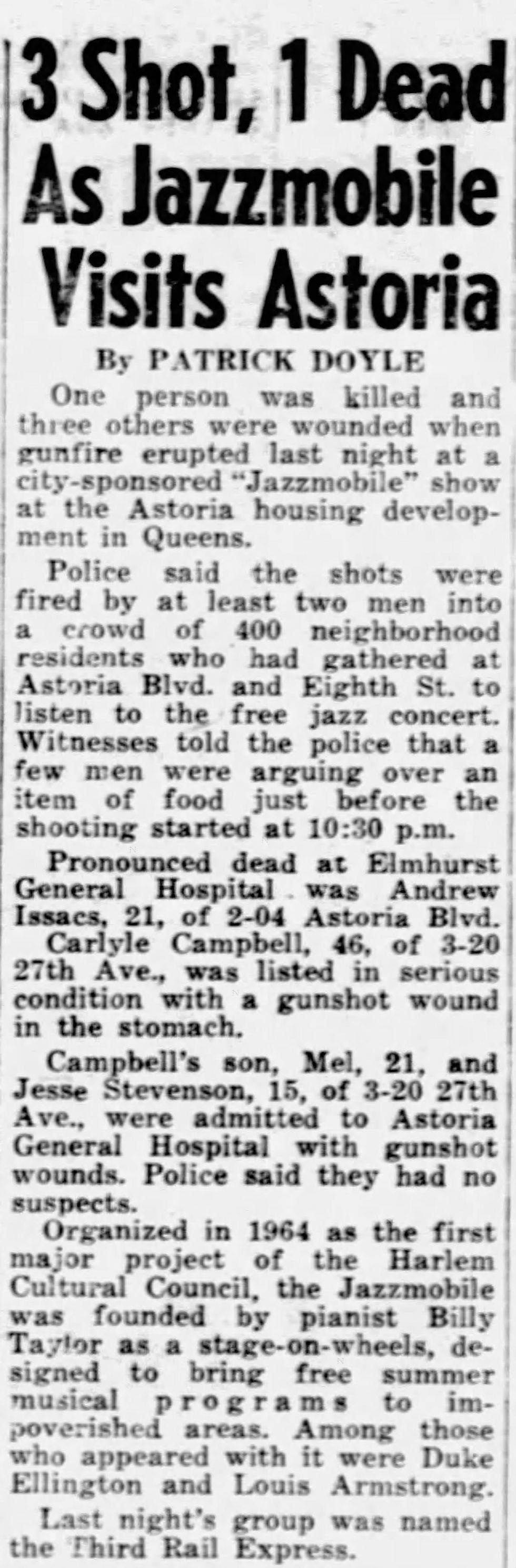

Outside their fifth-floor window, a city-sponsored Jazzmobile show was underway. It was supposed to be one of those summer nights that Queens kids remember fondly: music drifting through the hot August air, neighbors gathering at Astoria Boulevard and Eighth Street for free jazz under the stars.

The group playing that night was called the Third Rail Express. Jazzmobile had history—founded in 1964 by pianist Billy Taylor, it had brought Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong, and other legends into underserved neighborhoods. It was about joy, about community.

Until that night.

According to the papers, a fight over food broke out in the crowd of 400. Then, at least two men opened fire. By the time it was over, four people were shot.

Andrew Issacs, just 21 years old. He was pronounced dead at Elmhurst General Hospital. Andrew wasn’t just a name in the paper for Bill—he was his mentor, the man who ran the softball league Bill played in.

Bill and Kevin heard the gunfire, hit the deck, and were inside at the time watching Ralph Kiner interview George Foster. They lived. Andrew did not.

“It was like watching insects running away from Raid or Black Flag,” Bill remembers. “If I hadn’t gone up to watch Kiner’s Korner, I would have been right there.”

Bill admits he wasn’t a great student. “I hated school, and I was bad in school,” he says without hesitation. But Kiner’s Korner? That was an education he wanted.

He remembers Kiner asking Tommy Helms how he felt about being traded from the Reds to the Astros. Helms shrugged it off, but noted that slugger Lee May was blindsided. For Bill, that was journalism: real questions, real answers, no filter.

“Kiner taught me how to interview players. Do your homework before you go on the air. Always be professional,” Bill says. “No agenda. Just baseball.”

That stuck. And if you’ve read Bill’s work at MLB.com, you know he carries that same code: respectful, thorough, prepared. Just like Ralph.

For younger fans who never saw it, it’s hard to explain the magic of Kiner’s Korner. It wasn’t slick or polished. There were no social media soundbites or PR handlers lurking off-camera. It was just Ralph, a couple of players, and baseball.

Fair. Balanced. Human.

George Foster talking about his mother. Seaver and Cleon Jones reflecting on life off the field. And for a kid like Bill Ladson—who needed both an escape and a direction—it was something bigger than a postgame show. It was a roadmap.

And on that one night in 1976, it was a lifesaver. Literally.

Bill never got to meet Ralph Kiner. But if he had?

“Thank you for teaching me how to interview players. Thank you for reminding me to always do my homework. And thank you for saving my life.”

So here’s the thing: baseball isn’t just balls and strikes, wins and losses. It’s stories like this. It’s how a Mets postgame show could reach a kid in Queens, give him a career path, and keep him alive on a night when fate had other plans.

And that’s why, when I wear the KinersKorner.com logo, I don’t just think about Ralph or Seaver or Cleon. I think about all the people Ralph inspired with that show—the kids who stayed up late, grinning the moment The Flag of Victory Polka kicked in, the dads and moms who passed the game down, the young dreamers who learned to love baseball from a man who just wanted to keep talking about it. I see it in their eyes the instant they recognize that unmistakable logo on my shirt.

And yes, I think of Bill Ladson too, the kid from Queens, music lover, Munson fan, and baseball lifer, sitting in front of a TV in Astoria, ducking gunfire, and unknowingly being given both a safe night and a lifelong blueprint for journalism.

Somewhere up there, Ralph’s probably smiling.

Comments