My Conversations with Davey Johnson: Stories, Lessons, and R.I.P. to a True Baseball Mind

- Mark Rosenman

- Sep 6, 2025

- 6 min read

It’s a strange thing when history and heartbreak collide. Davey Johnson, who once stood at second base for the Orioles and lofted the fly ball that ended the 1969 World Series in the Mets’ favor — and who, nearly two decades later, sat in the dugout guiding those same Mets to their second (and still most recent) championship has passed away. He was 82.

If you’re a Mets fan, Davey’s fingerprints are all over the storybook. He was on the losing end of the Amazin’s miracle in ’69, then the mastermind behind the swaggering, 108 win season of 1986. Along the way, he managed everywhere from Tidewater to Tokyo to Queens to Washington, won more than 1,300 big league games, and collected Manager of the Year awards in both leagues. He had a player’s pedigree four All-Star nods, three Gold Gloves, and even a 43-homer season as a second baseman (yes, you read that right) but what always defined him was his mix of brains, boldness, and belief in his players.

Davey was one of baseball’s early analytics guys before anyone was calling it that, a math whiz who brought computers into the clubhouse. But he also had that old-school manager’s gut feel and a knack for letting his players be themselves , sometimes too much for the buttoned-up front office types, but exactly what that 1980s Mets circus needed.

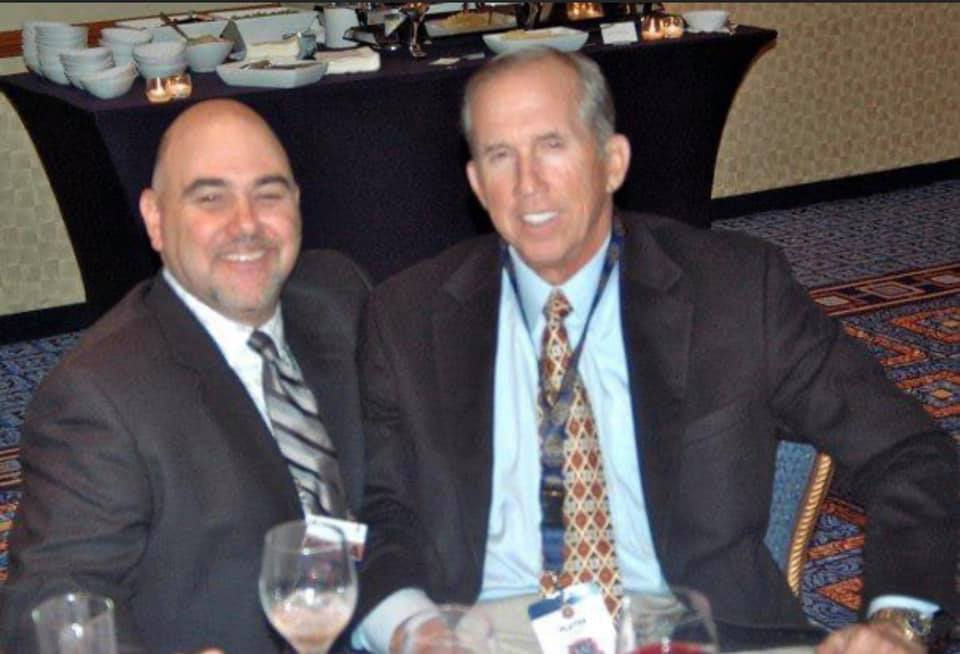

For all his milestones, though, what I’ll remember most are the conversations we shared over the years. Because behind the numbers, the trophies, and the headlines, Davey had a way of talking baseball and life that was equal parts candor, humor, and wisdom. And when he spoke, you listened.

Bat Dinner, January 24, 2012

When the Mets celebrated the 50th anniversary of the ’69 Miracle, Davey laughed as he told me about the chaos of that day. “Fifty thousand people came on the field, and I thought I was going to be trampled to death,” he said. “But you’re right , I started helping the Mets in 1969.”

And then, of course, he finished the job in ’86. When I asked him to put those two legendary teams in context, he didn’t hesitate. “When I was with the Orioles, we had a great ballclub. It reminded me a lot of what we developed here in New York in ’84, ’85, and ’86. A lot of talent, and some characters too.” Then he grinned, pushing back at the mythology. “We got a little bad rap. People hated us because we were good. There were a lot of stories written about how bad we were, but we weren’t as bad off the field as everybody dreamed up. We were only bad on the ball.”

That was Davey at his best , honest, self-aware, and a little defiant. He knew greatness when he saw it, because he’d lived it in two different uniforms, on opposite sides of history.

September 11, 2013 – Citi Field

The next year, when Davey was back in town managing the Nationals, we talked before a game on the anniversary of 9/11. He didn’t hesitate: “Every time I come here on 9-11, I make it a point to go over and visit. A firm that I was with lost almost 700 employees. You never forget that.” His voice softened when he said it , you could tell it was personal.

And yet, for Davey, New York always felt like home. “I love the fans,” he told me. “It’s a great baseball town. Everybody’s very intelligent here, so it’s challenging. I love it.” That was classic Davey , Queens as a second home, the Shea Stadium ghosts still alive every time he walked through Flushing.

He admitted he wasn’t a nostalgic guy, but the twinkle was there when he talked about seeing his old players in the broadcast booths. “Yesterday I got to sit down with Ron Darling. I don’t live in the past, but when you see those guys, you can’t help but think of all the little things that happened ,the struggles, the successes. It’s always great.”

From there he slid seamlessly back into manager mode, talking mechanics and rosters with the same energy he always had. He loved Harper’s swing: “He’s one of the strongest guys in baseball, but it’s not about swinging harder — it’s about being direct to the ball. He’s in a real good place right now.” And he was just as firm about team construction: “You can’t have any weaknesses on a ballclub. You don’t win a pennant with 18 or 20 guys. You win it with 25.”

That was Davey Johnson in a nutshell , honoring the past, fully immersed in the present, always preaching the value of every man on the roster.

WLIE SPORTSTALKNY Radio Show, December 16, 2018

One of the things I always loved about Davey was how unfiltered he could be. When we talked about his early days at Texas A&M, he laughed about the moment he realized he was in the wrong sport. “I was the point guard, and we were playing Bowling Green,” he told me. “I stole the ball, came back down the court, and went up to dunk. No-neck Nate Thurmond took two steps and swatted it into the cheap seats. Immediately, I said, I’m in the wrong sport.”

Baseball, thankfully, turned out to be the right one. Davey never got too sentimental about the details of his debut in 1965 against the White Sox, but he did remember the education he got running the bases against Whitey Ford. “I got a hit, he picked me off first. I got another hit and made it to second, he picked me off there. I got another hit made it to third, and Billy Hunter said, ‘If you get picked off here, you’re going to Thomasville, Georgia.’” Davey chuckled. “I learned fast.”

He spoke about those great Orioles teams of the late ’60s and early ’70s with both pride and humor. On his double-play partner, Mark Belanger: “Mark was the only shortstop I ever knew that didn’t wear a cup. That’s how good his hands were. Me, I needed two cups.” On Brooks Robinson: “Sometimes I had to remind Brooks to quit eating the sunflower seeds and move a little more off the line for bunts.” But when it came to Frank Robinson, the reverence came through: “As far as I’m concerned, he was the greatest influence on me as a teammate in my life.”

Whenever we circled back to 1969, Davey’s tone shifted. “We knew they were pretty good,” he admitted of the Mets. “But our scouts didn’t realize just how good Gary Gentry was. Once momentum turned against us, strange things can happen. And with that kind of pitching, you’re going to win.”

He talked about his trade to Atlanta, his 43-homer season, and even his early adventures with computer simulations. “I told Earl Weaver if he hit me second, we’d score 80 more runs. He threw it right in the garbage.”

And of course, we circled back to 1986. “The only way you resolve that,” he said of managing all those egos, “is 25 guys have to have roles. They have to know what their job is. Ability is one thing, but makeup is more important. That’s chemistry. And you know what? I never lost the team.”

When I pressed him on a dream matchup — the ’69 Orioles vs. the ’86 Mets — Davey gave the kind of answer only he could: “It would’ve gone seven games. Both had great pitching. But momentum matters. The ’86 Mets were a team of destiny.”

That was Davey Johnson. A math genius who could also talk about wearing two cups. A man who respected roles, respected his players, and believed in momentum as much as he believed in data. A guy who could laugh at his own wrong turns, and still remind you he was right when it counted.

For me, Davey Johnson will always be more than the man who made the last out of ’69 or the guy who handed the ball to Jesse Orosco in ’86. He was the bridge between two eras of Mets magic, the rare figure who could stand on both sides of history and laugh about it. He was blunt, brilliant, stubborn, loyal, and maybe just a little bit ornery in other words, the perfect New York Mets manager.

I was lucky enough to talk to him over the years, to hear his stories and his wisdom, and to see that twinkle in his eye when he talked about his players. And I’ll miss that. Baseball, and the Mets especially, were better because Davey Johnson was in the dugout. And if there’s a team of destiny somewhere beyond the clouds, I’d like to think Davey’s already penciling in the starting lineup. R.I.P. Davey.

Comments